I am giving you fair warning, right here in the very first sentence of this post: This one is about J.R.R. Tolkien. If that’s not your cup of tea, you won’t hurt my feelings if you go ahead and move along. Let me clarify, though, that while my feelings would not be hurt, you would be making an easily avoidable mistake and I would encourage you in the strongest possible terms to expand your literary horizons!

If I could only read one book for the rest of my life, I might choose Tolkien’s The Silmarillion. Not because it’s the best book I’ve ever read, but because I just love it very much. It isn’t for everybody; it isn’t even for everyone who has read and loved The Lord of the Rings. The Silmarillion was, in a sense, both the first and last thing Tolkien wrote. It is the collected mythology, so to speak, of Middle Earth. LOTR takes place in the Third Age, and The Silmarillion covers the First and Second Ages, which are dominated by elves.

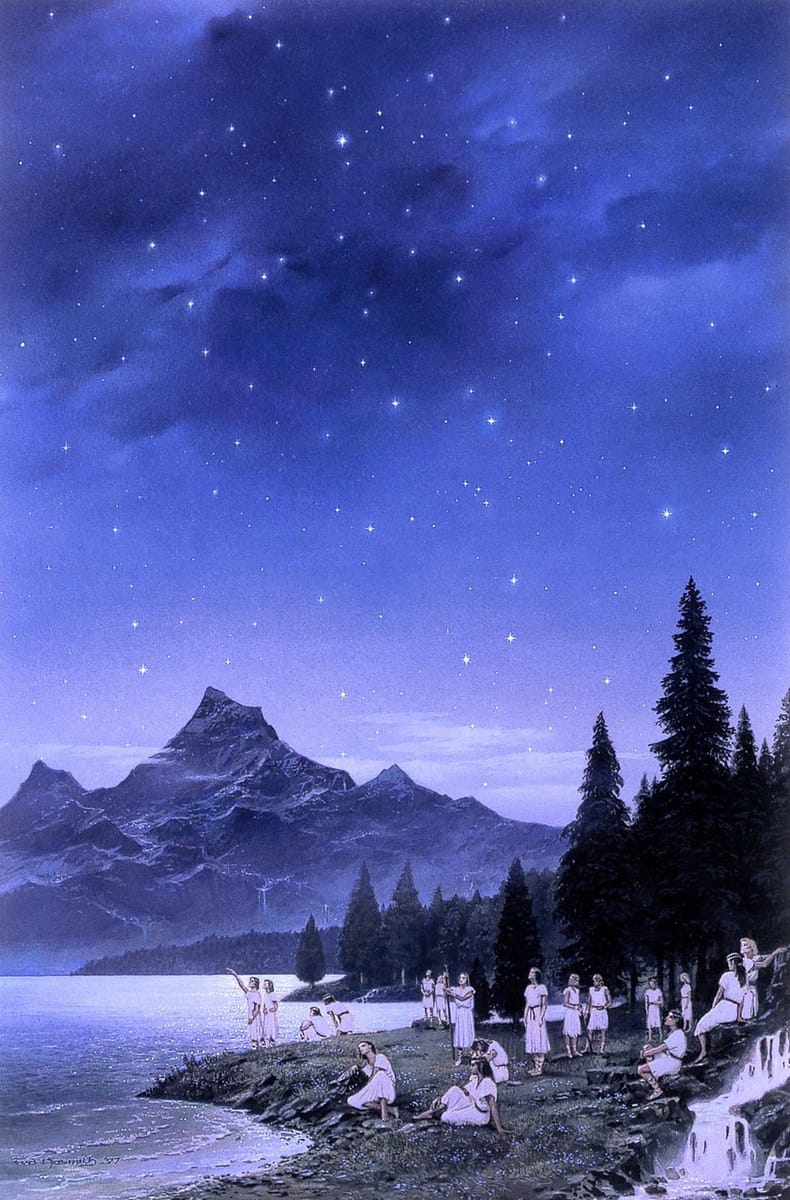

The first chapters deal with the creation of Middle Earth, and I do mean Creation with a capital-C. There is a God in Tolkien’s universe, though he doesn’t make an appearance in the more well-known books. Eru Iluvatar, as he is called, first creates the Ainur, which are basically gods and goddesses.

The way the Ainur work in Tolkien’s universe, there is an upper class and lower class. The upper class are called the Valar, and they truly are more like the gods and goddesses we know from Greek or Roman mythologies. They are elemental in nature, and Iluvatar effectively delegates the act of creating Middle Earth to them, reserving for himself alone the ability to create living beings, specifically elves and men.

Ok, I know that’s all very interesting and that you have already gone on Amazon and bought TWO copies of The Silmarillion, one for now and the other for when your first copy wears out from reading it so much. Stay with me.

What really stands out in Tolkien’s creation story is how Iluvatar shares his plans with the Valar: Through music. Iluvatar begins the music, and the Valar perceive his intent through the music’s themes. They are a part of the music, all in harmony together with Iluvatar. Except that one of the Valar, Melkor, isn’t satisfied. See, he is so taken with the music that he wants to make his own. Except that when he does, it clashes with the theme Iluvatar began, and the music descends into chaos.

Iluvatar begins again, and the second theme is even more wonderful than the first. But Melkor begins again too, this time with a less “noble” intent than before. This time, he begins to recruit other Ainur to his theme, rather than Iluvatar’s. Again chaos, and again the music has to start over. Eventually, Iluvatar’s music is triumphant, but Melkor and those Ainur who sided with him (including one Ainur named Sauron) are forever separated from Iluvatar, forever enemies of the Valar and the coming children of Iluvatar, elves and men. While I love the opening chapter of The Silmarillion because I think it’s beautiful, I also find it a very compelling portrayal of a perfect being’s downfall.

Christians have long hypothesized how exactly Satan’s fall came about. How does a perfect being sin, after all? I am not saying that Tolkien figured it out – I don’t think that’s the point of what he wrote. But I do think he understood something fundamental about the nature of desire: Good desires frustrated often lead to resentment and hatred.

I think Tolkien’s insight was that Melkor wanted a good thing that he couldn’t have. As Tolkien describes it, Melkor’s initial intent wasn’t to ruin Iluvatar’s music. Neither was it to create competing music. No, Melkor was moved by the beauty of Iluvatar’s music and he wanted to create something as beautiful. Is that a bad desire? No, it is not. I would suggest that it is actually a good desire. But desires that are not properly channeled can become twisted. All of the other Valar are willing to submit their music to Iluvatar’s; Melkor is not.

And so this good desire to make something beautiful has, at its heart, something that makes the desire impossible. Iluvatar’s music is not for himself, and the Valar’s part in it is not merely for themselves. Melkor, though, wants something that is entirely his own, something that can stand alongside Iluvatar’s music. He begins by wanting a good thing, but in a way that makes failure inevitable. I don’t know if Satan’s fall was similar, but it’s a pretty compelling scenario.

I find it particularly compelling because it is something each of us is prone to as well. We want something; we cannot have it. And our desire, if we are unwilling to relinquish it, festers and turns into anger, resentment, hatred. It happened to our first parents, who were asked a simple question: “Did God really say…” that made them wonder, “is he keeping something from us?” And their good desire (to be like God) was paired with an impossible demand (to be like God on their terms) and led to disaster.

I believe that, in the end, we will discover all of our good desires within the theme God is orchestrating. The question is whether we will submit ourselves to the music

Love this, Jack. There’s so much in Tolkien’s creation story I love and this lesson you’ve gleaned is probably the most important.

If I understand you correctly, it seems like trusting God's goodness and specifically, his intentions towards us are at the core of whether or not we surrender to the music.